Return to the Wards' Home Page

| On the long Memorial Day weekend, five of us visited the Sheldon Wildlife Refuge in northwestern Nevada. We found wide open spaces and interesting terrain to explore. |

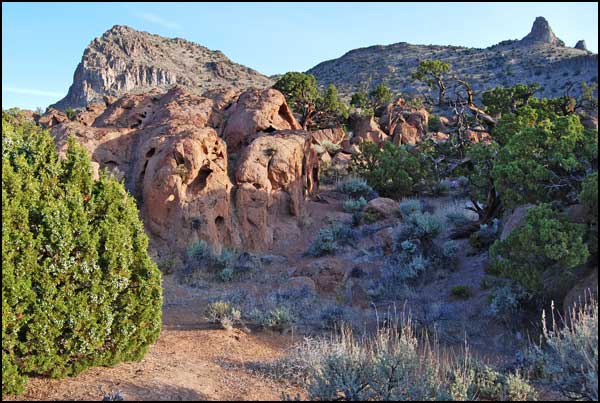

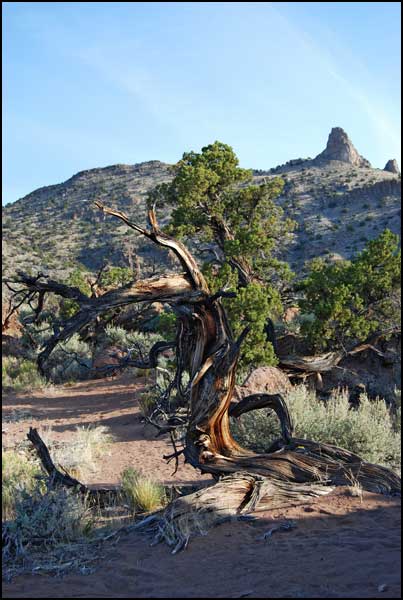

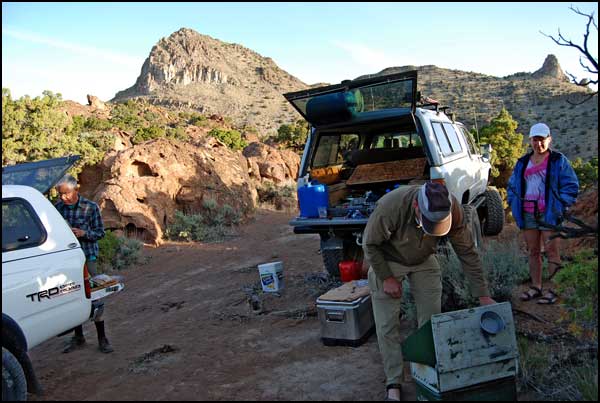

| We met Friday night at a site near Pyramid Lake. The knob on the horizon provided an easy landmark, still visible on the horizon in the dark when we arrived. We admired the weathered rocks and juniper trees in the morning light. |

.

.

|

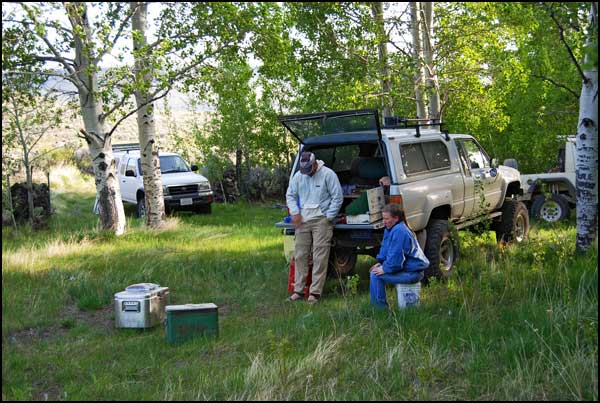

As usual, Martin was head chef. He prepared his deluxe oatmeal for breakfast. Another morning we had breakfast burritos. |

|

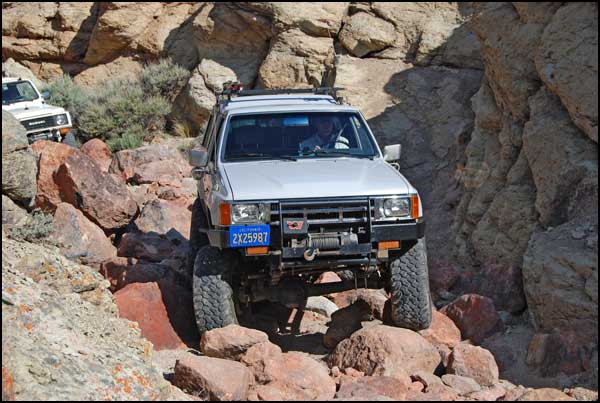

Although there was an alternate way out, Rick and Martin preferred the route through Mullen Canyon, which they had traversed before. |

|

Martin went first, Rick went second and Jim met us on the other side. |

|

This is

a road?

|

|

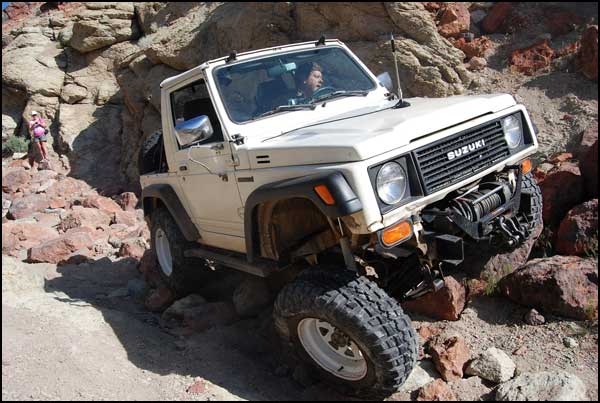

Look

carefully at that rear wheel.

|

|

Some people

would think this is a problem, but not Martin.

|

|

Martin simply

continued on his way after we all had a good look. One wheel spinning

in the air and the differential resting on the tip of a rock provided

much merriment.

|

|

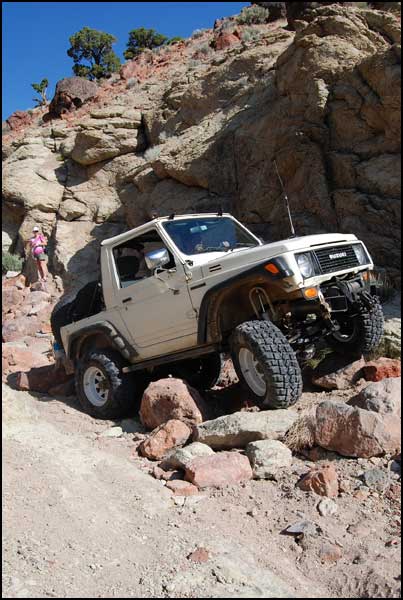

Rick's Suzuki

clambered over the rocks.

|

|

Rick manuevered

with care and no problem.

|

|

As we were

driving along, Cassandra spotted a Great Basin Collared Lizard sunning

on a rock. He remained still for multiple photos, allowing us a close

approach..

|

|

Our route

passed through High Rock Canyon, following the Applegate emigrant trail

that was opened by the Applegate Party in 1846 as a route to the Willamette

Valley in Oregon. In 1848 Peter Lassen opened a branch into the Sacramento

Valley. In 1849 it was mistakenly used by many gold-seekers as a shortcut

to California. It was not a bad route, but it was longer than the other

trails, with hostile Indians, and people ran out of supplies before

arriving at Lassen's Rancho on the Sacramento River. When an early winter

set in, many late-season travelers were rescued by the army and valley

settlers desirous of avoiding another disaster similar to that suffered

by the Donner Party in 1846.

|

|

The view

as we approached High Rock Canyon. Our dry winter made the dusty roads

even dustier.

|

|

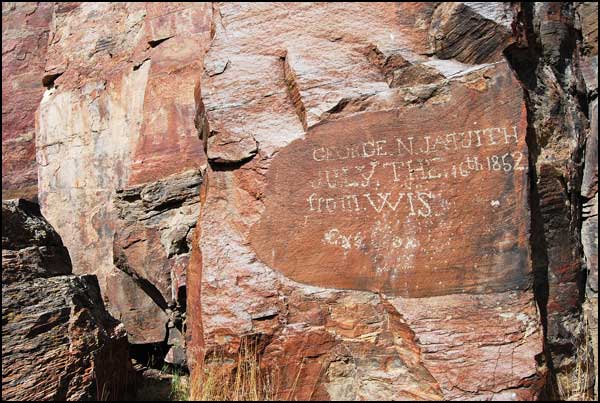

George J.

passed this way on July 16th, 1852. He would have been late in arriving

at the goldfields, if that was his intention, but gold-seekers no longer

used this route.

|

|

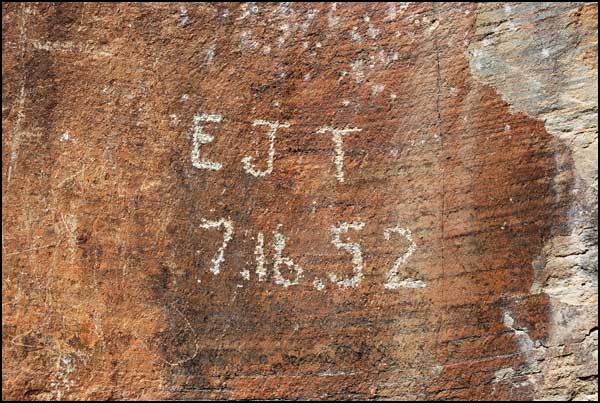

More likely

he and his friend E.J. were seeking the rich farmlands in Oregon. Their

names appear close together on the rock face, inscribed on the same

date..

|

|

This is

the route they were traversing. Our road is visible below.

|

|

Yellow Rock

Canyon is a side canyon.

|

|

We saw antelope

walking in single file on a trail near the bottom of a similar slope.

There were eight or more of them, and one of them appeared to be very

young.

|

|

This is

a typical view of our road.

|

|

We named

these outcroppings the Chocolate Cliffs.

|

|

We stopped

in a volcanic area for Martin to cook dinner for us, then we continued

on our way north..

|

|

Asters and

phlox were in bloom.

|

|

Sulphur

flower

|

|

Paintbrush

|

|

An unusual

salmon-colored paintbrush

|

|

Evening

primrose

|

|

We had no

sensation of being shut up in "dark defiles," but we weren't

traveling at twenty miles a day, day after day.

|

|

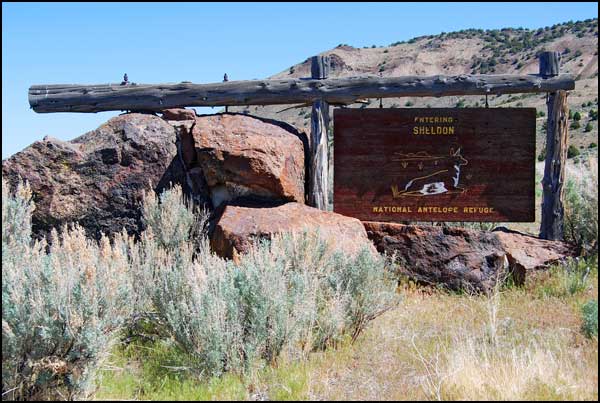

We entered

the Sheldon Wildlife Refuge from the south in the dark, following a

little-used dirt road with Martin and Rick navigating via waypoints

Martin had installed on his GPS. There was only a small sign indicating

the Refuge boundary. The above sign, photographed as we left the Refuge

at the west entrance, was constructed by the Civilian Conservation Corps

in 1931. At that time the National Antelope Refuge contained 34,000

acres. In 1936, the Charles Sheldon Antelope Range (or Game Range) was

established with 540,000 acres.

|

|

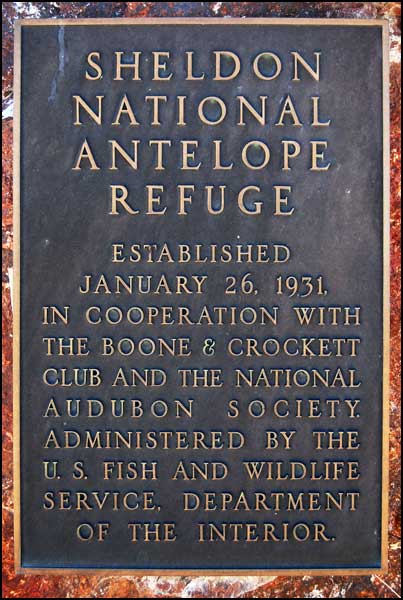

In 1976 the

original Antelope Refuge and the Charles Sheldon Antelope Range were

combined into the Sheldon National Wildlife Refuge. The approximately

575,000 acre refuge is administered by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service

as a "representative area of high-desert habitat for optimum populations

of native plants and wildlife." Visitors may wander the many dirt

roads, but camping is limited to designated areas.

|

|

East Rock

Spring Campground, which Martin unerringly led us to in the dark at

the end of a series of dirt roads, was surprisingly lush. It was surrounded

by a fence and could be used as a corral..

|

|

The surrounding

dry sagebrush steppe was in sharp contrast to our grassy campsite by

the spring.

|

|

The Refuge

has flat open expanses, narrow canyons and broad rimrock tables that

end abruptly in vertical cliffs.

|

|

The Virgin

Valley Mining District covers 67,000 acres of Refuge land. Several kinds

of rare opals are found here, including black, fire and wood opals.

Some of the mines are open to rockhounds who pay to search the tailings

or mine the banks. Opals may also be purchased in the mine gift shop,

but they are expensive.The Virgin Valley Campground is popular with

rockhounds and desert lovers who swim in the hot springs or fish in

the stocked Duferrena Ponds nearby.

|

|

Cassandra

spent about four hours sifting through the tailings of the Royal Peacock

Mine. She found a handful of small wood opals, with pretty colors that

were formed as wood and other organic matter petrified.

|

|

While Cassandra

mined, the rest of us drove to an overlook at Thousand Creek Gorge.

Martin climbed a nearby mound for an expanded view.

|

|

We had hoped

to hike in the Gorge, but there was too much brush and no defined trail.

This is the view to the southwest.

|

|

We walked

along the rim watching the changing patterns of light.

|

|

After driving

east to Denio Junction for fuel, we turned towards California. Our last

campsite was in a wide open grassy bowl at West Rock Spring Campground.

The temperature dropped below freezing at night.

|

|

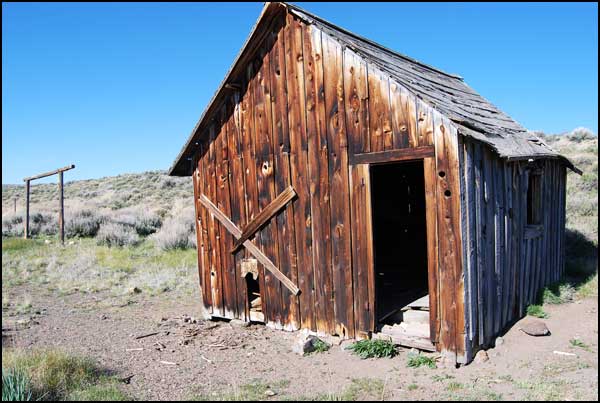

This shack

is over 100 years old. Property adjoining the campground is for sale:

40 acres for $45,000. The purchaser would be buying solitude. There

is a pond several miles down the road, so perhaps a fisherman might

be interested.

|

|

The hillside

nearby was riddled with large holes about 8 inches in diameter, each

with an extensive pile of dirt with indistinct tracks. We don't know

what made them, but later we read that badgers are common in the Refuge.

Note the large chunk of obsidian apparently dug up by the animal.

|

|

The hole in

this picture is at the top center behind the bright clump of grass.

The tracks are blurred, perhaps by age or wind. Facts to contemplate:

Badgers dig oval holes 7 inches high and 12 inches wide. The fan of

dirt may be 4 to 6 feet wide. The fans we saw were somewhat less, but

still impressive. Badgers will have many holes in an area, making it

appear that there are more badgers present than there really are. There

is usually no scat or food scraps visible, which was true of the area

we observed. On the other hand, kit foxes have tall oval holes 7 to

12 inches in diameter with good-sized dirt mounds at the entrance and

with multiple entrances. They may appropriate badger holes. In the spring,

food scraps and scat may indicate an active den with pups.

|

|

We left

the campground via the Catnip Mountain Loop.

|

|

Along the

way we saw several death camas lilies in a volcanic rock garden.

|

|

We also saw

three different colors of paintbrush growing right next to each other.

|

|

Martin's truck

raised a plume of dust as he drove west through the area called Little

Sheldon, part of the original Antelope Refuge.

|

|

Wild horses

and pronghorn antelope roamed in the adjacent fields. Wild horses and

burros are considered non-native and are subject to periodic roundups

to be offered for adoption. Most tourists find it exciting to see wild

horses, and it has been suggested that they should be considered part

of the wildlife.

|

|

As we left

the Refuge, Rick had a flat tire which he quickly repaired.

|

|

We stopped

in the town of Cedarville to air up. The remainder of our trip was on

paved roads, a feature we hadn't seen since Friday night.

|

|

There was

no date on the building, but it was obviously historic.

|

|

Another adventure

came to a close, but we were left with memories of wide open spaces,

unexpected views, wildlife, wood opals, wildflowers, mysterious holes,

dust plumes and good companionship.

|